'His Majesty’s Spanish Flock. Sir Joseph Banks and the Merinos of George III of England'.

H.B. Carter, 1964.

Angus and Robertson. First published in 1964.

H.B. Carter and Merino sheep arrive at Leeds University

This story starts when I was a Lecturer in the Department of Agriculture at the University of Leeds from 1959-1968, and Harold Carter arrived 'out of the blue' in 1965 with a flock of Merino sheep which were pastured at the University farm at Headley Hall.

None of us on the staff were told anything about them by our Head of Department, Professor T.L. Bywater, and certainly none of us who lectured in 'Animal Husbandry' knew anything about Merinos. I can only remember looking at them once, as they and Carter were 'off the radar' on visits to the farm with students. The sheep never seemed to move from their allocated area at Spen farm, unlike the other sheep which rotated over a wide area on the farm as they were integrated into a mixed farming operation.

So I was interested to learn from my former colleague, Senior Lecturer Geoff Boaz's book (see later) that the sheep flock was made up of purebred Merinos and some Cheviot x Merinos. The latter must have been produced at the University of Edinburgh's 'Animal Breeding Research Organisation' (ABRO) as part of Carter's research.

Meeting Carter

I can only remember brief meetings with Carter outside the Textile Department on my way to lunch at the Senior Common Room. I can't remember him ever being in the Agriculture Department. Carter assumed that (as a sheep enthusiast) I would know all about Merinos, and hence would have an interest in his recently published book on His Majesty's Spanish Flock. He lent me a copy which I soon returned unread, as Merino history and mad English Kings were not my priority at the time.

I was more concerned about getting out of the place, after the University Grant's Committee had declared that Leeds, Glasgow and Oxford should close down their 'Agriculture' degree courses and teach more 'Agricultural Science'. This was the start of a major 'shambles' in agricultural eduction in UK, the effects of which have been very long lasting which I've been happy to watch from afar.

I remember when I started asking who Carter was, and how we had this world expert on Merinos in the Textile Department, with his weird sheep grazing at the University farm, I was told very much on the quiet, that he had overstayed his welcome at ABRO, and had landed in our midst to find a home.

Aussie v Kiwi

Knowing the personality of H.P. (Hugh) Donald, Director of ABRO, it wasn't difficult to suspect that the relationship between Carter and Donald would have had problems. Donald would in a very short time have seen Carter as a threat. And after decades in New Zealand, I can well imagine our 'trans-Tasman rivalry' being alive and well between them.

One of Donald's staff described him as 'acerbic' till he tool a liking to you, and then you were 'great mates'. Donald had been at Massey College in New Zealand (now Massey University) with C.P. McMeekan (and both had similar personalities). I can see now that they would have made a very good pair - a pair that inevitably had to go their separate ways, which they did.

Comment from Dr Michael Ryder

Dr M. L. Ryder is a biology graduate of Leeds University, but took his research degrees in the Textile Department and began his career at the Wool Industries Research Association. He spent three years as Senior Lecturer in Wool at Armidale in NSW (1960-62) and then 25 years in Edinburgh, first at the Animal Breeding Research Organisation and latterly at the Hill Farming Research Organisation. He is now an independent author and textile fibre consultant based in Southampton. Dr Ryder is perhaps best known for his use of textile remains to follow the evolution of different fleece types, and this forms a theme of his book Sheep and Man (Duckworth, 1983). ISBN 0-7156-1655-2.

Dr M. L. Ryder is a biology graduate of Leeds University, but took his research degrees in the Textile Department and began his career at the Wool Industries Research Association. He spent three years as Senior Lecturer in Wool at Armidale in NSW (1960-62) and then 25 years in Edinburgh, first at the Animal Breeding Research Organisation and latterly at the Hill Farming Research Organisation. He is now an independent author and textile fibre consultant based in Southampton. Dr Ryder is perhaps best known for his use of textile remains to follow the evolution of different fleece types, and this forms a theme of his book Sheep and Man (Duckworth, 1983). ISBN 0-7156-1655-2.It was from Armidale that he returned to ABRO to the staff vacancy created by Carter's departure, and he remembers that Donald forbade ABRO staff to let Carter take any microscope slides etc., with him when preparing to leave for Leeds. Ryder said the technician in charge of the slides was put in the embarrassing situation of having to refuse Carter when he came asking for items. At the same time Donald asked Ryder not to work on the Merinos, although he made more and more observations on them over time. Ryder described his contacts with Carter as meagre and unhappy.

Why didn't Carter join the Leeds Agriculture Department?

On paper, Carter would have fitted much better into the Agriculture Department at Leeds, but presumably he didn't get an invitation from Bywater. The prospect of his sheep arriving and taking over the 25 acres previously used by Boaz's research flock for fat lamb production, must have involved some decisions that I was not privy to, as Boaz was very protective of his sheep work. He would certainly not let me get involved in any of it having arrived in the Department with a Ph.D in sheep breeding.

It would be interesting to know how much pressure Bywater was put under to take Carter and his sheep, and how high up the tree this came from. Donald and Bywater were certainly not bosom pals, but Bywater was very interested in breeding and genetics, so maybe he saw some kudos from having these unique sheep on the farm, without giving shelter to their supervisor.

I remember that the feeling around the place was that both Carter and his sheep were definitely becoming a nuisance, and neither were ever referred to in friendly terms. In any case, none of us in the Agriculture Department knew anything about wool, although we lived in the heart of the UK textile industry. Wool kept a sheep warm and had to be 'clipped' once a year - and that was about our total knowledge.

There was certainly no liaison between the School of Agriculture and the Textile Department. Dr Michael Ryder reinforced this by reminding me of the work of Marca Burns, F W Dry, Graham Priestly, Harry Side and Peter Speakman (son of J.B. Speakman), all of whom worked on wool in the Textile Department before the age of synthetic fibres.

There was also no contact between the Agriculture Department and The Wool Industries Research Association (WIRA) in Headingly. I passed it every day and once even called in to a very warm welcome by A.B. Wildman, head of the Wool Biology section and was amazed at their work and relevance it had to the wool industry worldwide.

Carter and Dry in residence at Leeds

We started to view Carter in the same way we did Dr F.W. (Daddy) Dry, who was also holed up in the Textile Department on one of his many trips back to Leeds from New Zealand. For the 20+ years Dry was at Massey, Dr George Wickham told me he kept his house in Leeds for when he had his visits back there. Everyone referred to him as 'Daddy' (not to his face) as Mrs Dry called him that (see my blog on Dr Dry).

It's only now that I realise that with Dry and Carter around the Textile Department at the same time on the same campus, we had the world’s top experts on skin follicles, with Dry at the coarse end and Carter at the Superfine end! What a photo that would have been for the archives!

On Dry's last visit to Leeds before I left in 1968, he must have got evicted from the Textile Department and Bywater must have been persuaded to take him in, as in Dry's book, he thanks Professor Bywater of 'The School of Agricultural Sciences' (one of the new name they came up with to survive) for his support.

I was thrilled when I learned that Daddy had taken over my office after I left, so clearly they must have flown the Textile Department. George Wickham when he did his Ph.D in the Textile Department remembers Dry being housed in a prefab beside the big flash Textile building, which George says was knocked down, probably leaving Daddy and his fibres open to the sky! It was an effective way to get rid of him!

Merinos at Leeds

In Geoff Boaz's book (see later) he says that the Merino sheep were under Carter's total control after he arrived from Edinburgh in 1965, but after he retired in 1970, the flock came under the control of the Leeds University Farm.

It was interesting that Farm Manager, John Dalley told me he was not allowed any say regarding the management of the sheep, but remembers them being a real problem with flystrike and footrot which Fred Cass the shepherd (who rode his bike around the farm without a dog) would have to attend to. John remembers the Department lecturer in Veterinary Science, Ken Towers being heavily involved in their care.

So apparently Boaz took over care of the sheep until they ran into problems with Johne's disease, (reported in Boaz's book). Boaz doesn't say what year this happened. The Johne's outbreak triggered the decision to slaughter all the sheep because they were too big a risk to the two dairy herds on the farm (one Red Poll and the other Jersey).

Boaz also reported in is book that some crossbred sheep went to a local farmer and a couple of rams had been used by Professor Care at the University for research on the ability of skin to heal quickly. So these missed the chop. Care must have recognised that Merino skin heals quickly after the mutilation they can get from shearing and the practice of mulesing to prevent blowfly attack around the britch.

Boaz also mentions that Merino rams had been used at the MAF Experimental Husbandry Farms (EHFs) for crossbreeding trials, so presumably they were supplied from the Leeds University flock. Our nearest EHF farm was at High Mowthorpe on the Yorkshire Wolds which we visited regularly with students.

Carter in the Leeds University Textile Department

Presumably, after falling out with Donald at ABRO, Carter must have persuaded Prof Speakman, Head of the Textile Department to find him an office. Carter and Speakman were old friends, and Speakman was a major speaker at the 1955 International Wool Textile Conference in Sydney. Charles Massy in his book (see later) stresses that Carter and Speakman were kindred spirits and almost visionaries on the need to take a 'holistic' approach to improving the Merino fleece. Their views were ignored for more than four decades according to Massy.

Former staff of the Textile Department contacted by Tim Johnson, former lecturer in the the School of Agricultural Sciences said they only knew Carter as 'a name on a door', and he certainly did no research in the Department that they were aware of.

Carter certainly managed to get himself some respectable titles. The archives at Leeds show this in the University Calendar:

- H.B.Carter, Hon. Lecturer in Textile Chemistry 1963/64 - 1969/70, latterly in that period as Hon Fellow in Textile Chemistry.

A photo caption clue

This is in the incredible book ' The Australian Merino' by Charles Massy (second edition 2007), Random House Australia, ISBN 978-1-74166-692-2. The book is an outstanding example of dedicated scholarship over what must have taken many years of research and travel, all around the world where there was the slightest chance of finding a Merino type sheep. The book has 1262 pages and weighs 3.6kg. If there was ever a book that should be available on an e-reader, this must be it, as it's impossible to read it on your lap and certainly not in bed!

Massy talks of visiting Carter on his trips to UK and wanting him to write the Foreword to the book, but sadly although Carter had been willing, his illness prevented this. Instead he got Dr Ken Ferguson to write about Carter for the foreword. It's here on the page before the foreword that the photo of Carter at Leeds appears - presumably taken by Massy. I can recognise the old shed at Spen farm.

It's in the caption to this photo that we find a wonderful clue to what Carter did at Leeds. Here's what it reads:

It's in the caption to this photo that we find a wonderful clue to what Carter did at Leeds. Here's what it reads:'Harold Carter (on the left) and David Knight examining a fine-wood Australian-blood ram at the Leeds research station, UK - c1965. David Knight, then Director of the UK's largest top maker Sir James Hill & Sons (and later Vice President of the British Wool Federation), was a pioneer of Objective Measurement and Total Quality Management in British mills.

In 1965, he was able to place Harold Carter with three assistants, in a laboratory on one of Hill & Co's Leeds mills. This was a pioneering effort to link biological and genetic knowledge in industry performance of the wool fibre; and only pre-empted by the Brno Sheep Breeders' Society in 1814.'

So for those in the Leeds Textile Department who only saw Carter as a 'name on a door' - and suspected he did little for his pay, they should have known that 'he were 'down in't mill'!

With three assistants he must have got through a pile of work which no doubt is in his personal archives, described to me as meticulously documented, by his son Professor Richard Carter of the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Edinburgh's Ashworth Laboratories .

Tribute by Dr Ken Ferguson

Dr Ken Ferguson, BVSc., Ph.D., FACVS.

Harold Burnell Carter (1910-2003) graduated in 1932 from the Faculty of Veterinary Science at the University of Sydney and the next year he was appointed as a Research Officer in the Australian Estates and Mortgage Company on their NSW properties with field headquarters at the Tyrie Station, Dandaloo in Western NSW with bench space at the F.D. McMaster Laboratory in the grounds of the Sydney Vet school.

He resigned in 1936, concluding after three years of visiting sheep studs, that a coherent base of fundamental research was needed to improve the quantity and quality of Australian wool production. Such information was also required to breed resistance to such conditions as fleece rot and blowfly strike.

He was appointed Walter and Eliza Hall Fellow in Veterinary Science and with a research remit to study the biology of the skin and fleece, with special reference to the Merino. There had been no such work done in Australia and he decided to start with visits to South Africa, Great Britain and the USA. In Leeds he collaborated with A.B. Wildman to outline a concept of the hair follicle group applicable to all sheep.

On his return to Sydney he as again located at the McMaster Laboratory where he established a histology unit to continue his study of the wool follicle while keeping in contact with various studs taking fleece and skin samples for analysis. He persuaded the Chief of his Division, Lionel Bull to establish housing for sheep in single pens with facilities for feed mixing, parasite analysis and a surgery.

Carter's ability to convince CSIRO of the need for these facilities extended to planning their postwar expansion and relocation to a new site at Prospect west of Sydney. This was based on the intent to counter increasing competition from cotton, synthetic fibres and alternative land uses such as cattle and crops. At that time wool accounted for over 50% of Australia's export income and had a greater diversity of qualities that most agricultural products.

Despite his role in planning the new facilities and his extensive knowledge of the wool industry, Carter was not appointed Officer in Charge of the Prospect Laboratory, possibly because he did not agree to the exclusion of genetic research from the Prospect research programme.

In 1954 he resigned from CSIRO to accept a senior position with the Animal Breeding Research Organisation in Edinburgh. There is little doubt that Harold Carter was the most important figure in establishing the post-war biological research facilities for the wood industry in Australia, and leading the research on the histology of the wool follicle'.

Richard Carter's memories of his father's work in Australia

Unless you have seen the endless horizon and sky of outback Australia, it's hard to realise the effort involved in visiting sheep stations, some the size of European countries. Richard remembers his father talking about journeys by air on Douglas DC3 and Dakota planes which pioneered outback air travel. But Richard says most of his father's travel was done in a grey, battered, Chevrolet truck which were robust enough for the long dusty farm roads and tracks between Sydney and Adelaide and beyond. Richard says ex army WWII Jeeps were very popular on outback farms too.

Publications

A few selected papers where Carter was joint author 1954-58.

A few selected papers where Carter was joint author 1954-58. Published in the Australian Journal of Agricultural Research.

Reprints were always had green covers. Age has faded these.

Carter was a very accomplished researcher as you can see from some of his published papers:

- Belschner, H. G. & Carter, H.B. (1936). Fleece charasteristics of Stud Merino sheep in relation to the degree of wrinkliness of the skin of the breech. I, II and III. Aust. Vet. J. 12: 43-55, 80-92, and 13: 16-31.

- Wildman, A.B., Carter, H. B. (1939). Fibre follicle terminology in the Mammalia. Nature, 144: 783-4.

- Carter, H.B. (1939). Fleece density and the histology of the Merino skin. Aust. Vet. J. 15: 210-213.

- Carter, H.B. (1939). A histological technique for the estimation of the follicle population per unit area of skin in sheep. J. of Council for Sci. & Ind. Res. (Aust) 12(3):250-258.

- Carter, H.B. (1940). Some fundamental aspects of the structure of the Merino fleece. Aust. J. Sci. 2(5): 143-146.

- Carter, H. B. (1941). The influence of plane of nutrition on the growth of skin in the Merino. J.Aust. Inst. agric. Sci. 3: 101-102.

- Carter, H. B. (1943). Studies in the biology of the skin and fleece of the sheep. 1. The development and general histology of the follicle group in the skin of the Merino. Bull. Coun. scient. Ind. Res., Melb., No. 164: 220, 26, 227.

- Carter, H. B. (1955). “The Australian Merino”. NSW Sheepbreeders Association.

- Carter, H. B. (1955). The hair follicle group in sheep. Anim. Breed. Abs. 23: 101-116.

- Ferguson, K.A., Schinckel, P.G., Carter, H.B. & Clarke, W.H. (1956). The influence of the thryoid on wool follicle production in the lamb. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 9(4): 575-585.

- Carter, H. B., Clarke, W. H. (1957). The hair follicle group in the skin follicle of Australian Merino sheep. Aust. J. agric. Res. 8: 91-108.

- Carter, H. B., Clarke, W. H. (1957). The hair follicle group and skin follicle population of some non-Merino breeds of sheep. Aust. J. agric. Res. 8: 109-119.

- Carter, H.B. (1958). The farmer, the gene and the fabric. J. Bradford Textile Soc., 1958-59. 22-23.

- Carter, H.B., Dowling, D. F. (1954). The hair follicle and aprocrine gland population of cattle skin. Aust. J. agric. Res. 5: 745-754.

- Carter, H.B., Hardy, M. H. (1947). Studies in the biology of the skin and fleece of sheep. 4. The hair follicle group and it’s topographical variations in the skin of the Merino foetus. Bull. Coun. Scient. ind. Res., No 215, pp 41.

- Carter, H.b. & Henshall, Audrey S. (1957). The fabric form burial (Cluniac Priory of St, Mary, Thetford, Norfolk). Medieval Archaelogy, I, 102-103.

- Carter, H.B., Turner, Helen N. & Harvey, Margaret H. (1958). The influence of various factors on estimating fibre and follicle density in the skin of Merino sheep.Aust. J. Ag. Res, 9 (2): 237-251.

- Short, B.F., Fraser, A.S. & Carter, H.B. (1958). Effect of level of feeding on the variability of fibre diameter in four breeds of sheep. Aust. J. Ag. Res, 9 (2): 229-236.

- Carter, H.B.1958). The farmer, the gene and the fabric. J.of Bradford Text. Soc. 1958-1959, 22-23.

- Carter, H.B., Tibbits, J. P. (1959). Post-natal growth changes in the skin follicle population of the New Zealand Romney and N-type sheep. J. agric, Sci., Camb. 52(1): 106-116.

- Slee, J. & Carter, H.B. (1961). A comparative study of the fleece growth in Tasmanian Fine Merino and Wiltshire Horn ewes. J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 57(1) 11-19.

- Carter, H.B. (1961). Taxonomic and experimental significance of the hair follicle arrangement in mammals. Bul. Brit. Mam. Soc., 17:5-6.

- Slee, J. & Carter, H.B. (1962). Fibre shedding and fibre follicle relationship in the fleeces of Wiltshire Horn x Scottish Blackface sheep crosses. J. agric. Sci, 58(3):309-326.

- Carter, H.B. & Slee, J. (1962). An unusual bi-paternal litter in sheep from a natural double mating. Nature, 194: 215-216.

- Carter, H.B. (1963). Protein fibres: Production. Text. Rev. 1963.

- Carne, H.R., Lloyd, L.C. & Carter, H.B. (1963). Sqamous carcinoma association with cysts of the skin of Merino sheep. J. Path. & Bact. 86(2): 305-315.

- Carter, H. B., (1964). The role of the skin in relation to the adaptation and the production of wool in the sheep. Proc. Aust. Soc. Anim. Prod. 5.

- Carter, H.B., (1964). His Majesty's Spanish Flock. Angus & Robertson, Sydney.

- Carter, HB., (1965). Variation in the hair follicle population of the mammalian skin. In: Lyne & Short, eds. Angus & Robertson, Sydney.

- Carter, H.B. (1967). The Merino sheep in Great Britain. Text. Inst. & Industry March 72-75, April 97-99.

- Carter, H.B., (1968). The future of Merino wool growing. J. Bradford Text. Soc., 57-64.

- Carter, H.B. (1968). The future of Merino wool growing. J. Bradford Text. Soc., 57-64.

- Carter, H.B., (1969). The historical geography of the fine-woolled sheep (1) & (2). Textile Institute & Industry, 7: 15-18, 45-48.

- Carter, H.B., Onions, W.J. & Pitts, J.M.D. (1969).The influence of the origin on the stress-strain relations of wool fibre, J. Text. Inst. 60(10) 420-429.

- Carter, H.B., Terlecki, S. & Shaw, I.G. (1972). Experimental Border Disease of sheep: Effect of infection on primary follicle differentiation in the skin of Dorset Horn lambs.

- Carter, H.B.(1970). Sir Joseph Banks and the plant collection form Kew sent to the Empress Catherine II of Russian, 1795. Bull. Brit. Museum (Natural History). Historical series 4(5): 283-385.

- Carter, H.B. (1979). The sheep and wool correspondence of Sir Joseph Banks 1781-1820. Vol 2 of The Sir Joseph Banks Memorial Act 1945. Angus & Robertson 1962.

- Carter, H.B. (1979). The Sheep and Wool Correspondence of Sir Joseph Banks, 1781-1820. Library Council NSW/British Museum (Natural History), London.

- Carter, H.B., Diment, Judith A., Humphries, C.J. & Wheeler, A.(1981). The Banksian natural history collection of the Endeavor voyage and their relevance to modern taxonomy. In History in the Service of Systmatics (Ed Wheeler & Price) London.

He was appointed Director of the Banks Archive Project at the Natural History Museum and edited The Sheep and Wool Correspondence of Sir Joseph Banks 1781-1820. This publication became a prelude to the publication of other groups of Banks's voluminous correspondence, including a definitive biography on Banks published by the British Museum.

Honorary Award

The degree of Doctor of Veterinary Science (honoris causa) was conferred in absentia upon Harold Burnell Carter at the ceremony held at 11.30am on 1 March 1996.

Citation:

Presented by the Acting Vice-Chancellor and Principal Professor D J Anderson, Chancellor.

Harold Burnell Carter was educated at the University of Sydney, graduating with the Bachelor of Veterinary Science degree in 1933. Awarded a Walter and Eliza Hall Fellowship in Veterinary Science, he studied the skin and wool of Merino sheep at CSIRO McMaster Laboratory within the grounds of this University.

His research provided our basic knowledge on the embryology, growth, development and genetic variation in the structure and function of the skin and the wool follicle. This work led to major improvements in wool production and contributed greatly to the economic development of Australia.

From his studies on the genetic selection of Merino sheep, Harold Carter discovered that it was the 18th century scientist, Sir Joseph Banks, who had arranged for merino sheep to be transported to Australia. This led Carter to undertake detailed historical research into the life and works of Banks.

His research was carried out under the auspices of the Natural History Department of the British Museum and resulted in a comprehensive review of Banks' contributions to science. Between 1764 and 1820 Joseph Banks wrote some 40,000 letters.

With Carter's painstaking collection of this scattered correspondence and other archival material, Joseph Banks emerged as the key figure in the growth of natural sciences in Britain at the end of the 18th century.

Harold Carter, in his 87th year, is still the Director of the Banks Archive Project of the Natural History Museum in London. He has published many papers and several books on Joseph Banks including: His Majesty's Spanish flock: Sir Joseph Banks and the Merinos of George III of England and The Sheep and Wool Correspondence of Sir Joseph Banks 1781-1820. Harold Carter has achieved international scholarly standing in two different fields, science and history.

Chancellor, Harold Carter cannot be with us today so I present to you Dr Kenneth Ferguson, a life time colleague of Dr Carter's and formerly Director of the Institute of Animal and Food Sciences of the CSIRO to receive the degree of Doctor of Veterinary Science (honoris causa) on behalf of Harold Burnell Carter.

The Order of Australia

When in his 90s H.B.Carter was awarded the Order of Australia. Richard Carter says his father was too infirm to go back to Australia to accept the medal in person, but the Government sent him the appropriate robes in which he was photographed, and the medal - shown below (both sides). Richard is not sure why the 'A M' was embossed on the box lid but he thinks it could be an example of his father's dry sense of humour - simply denoting 'Australian Medal'.

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE)

Carter was nominated for this award on 24 November 1960, and surprisingly the first name on the list of nominees is one H.P. Donald.

Back track - why Carter resigned from CSIRO

This is a fascinating part of the story, as why on earth would anyone who had done so much fundamental work on the Merino, and put in the hard yards on the McMaster and Prospect laboratories, want to leave and go to the frigid climes of Scotland?

Comments by Dr George Wickham

George Wickham, a former Massey wool scientist who did his PhD at Leeds Textile Department around 1954 was familiar with Carter's work, and told me that he was told by a former colleague of Carters, that the mountain of his unpublished data left at Prospect was viewed as 'a negative' by the new Director, Dr Ian. W. McDonald.

This seems an unjustified claim as Carter would not be the only scientist who had left a position with unpublished data, especially in the biological sciences, as it's not possible to have all your data analysed and have everything written up at the end of each project. It often takes years to complete this and a deal of understanding from your new boss. The scientific world is littered with research that was never written up, most of it ending up in land fills.

Comments by Dr John Kennedy

J0hn Kennedy reported that McDonald had been a contemporary of Carter's at the University of Sydney vet school, and returned from Babraham, Cambridge University in UK to take the Prospect job. In the biography of Sir Ian Clunies Ross written by Marjorie O'Dea, she relates that it was Sir Ian who by then was Chairman of CSIRO who decided that Carter was not a suitable appointment to be Officer-in-Charge of the Prospect lab, even though he had worked hard on its planning. Professor C.W. Emmens was Prospect Officer-in-Charge for a couple of years before McDonald came back from UK.

John Kennedy also said that the other big job Carter did while at Prospect was to edit the sheep and wool correspondence of Sir Joseph Banks which was published with the help of the State Library of NSW, so he was clearly building up a head of steam for his future work.

Comments by Charles Massy

Charles Massy in his book describes in great detail how Carter's view on the need for a 'broad holistic approach' to research was ignored and caused great frustration for him. Massy wrote:

'Carter was the first modern scientist to form a bridge between the practical technique of leading breeders and classers and the science of biology and genetics, and of textile needs.'

Ian Clunies-Ross invited the world famous American geneticist J.L. Lush to visit CSIRO and advise on a plan for animal breeding research. This led to the splitting off of genetics from the skin and wool biology work and this may have been a major reason for Carter looking to get out.

Whatever the reason, Carter took off soon after the Prospect Lab's opening to the Animal Breeding Research Organisation (ABRO) in Edinburgh, funded by the Agricultural Research Council (ARC). This institute worked in close relationship with the Institute of Animal Genetics in the University of Edinburgh. The Carters and their young family would certainly have faced a massive change in environment - both geographical and social!

I have great empathy for Carter on this issue, as I did the same thing but in the opposite direction. You may think you know what things will be like at the other end, but they never are, and you worry about how your children will settle in new schools, as they have 'funny accents' which can cause problems in this intolerant world. Australians going to UK would get less 'stick' than 'Poms' coming to Australia or New Zealand.

Apparently a lot of Carter's colleagues at Prospect wanted him to stay, and from the amount of work he did there (see published papers and Massy's book) it's apparent he was going to leave a massive vacuum in their programme - work that clearly could not be carried on at ABRO.

Comments by Richard Carter

After talking to a former ABRO colleague of his father's, it appears that Carter's appointment to ABRO was not simply an invitation from HP Donald to join his team. It seems that Carter was headhunted by Lord Rothschild and Sir Gordon Cox who were in the top tier of the Agricultural Research Council (ARC), and who continued to support Carter during his ABRO troubles. Richard describes this as his father may have been 'parachuted in by them as a desirable addition to ABRO'.

The way Donald behaved subsequently to Carter would make you think that he wasn't very happy about the move, as he certainly did much to make Carter's life difficult, so that in a few years, Richard describes his father's situation as being 'non-operational', as Donald held the purse strings.

My experience is that University Departments and Research Stations can be vicious places where there is much child-like behaviour based on jealousy. ABRO seems to have a good dose of this and Carter was the unfortunate recipient.

Massy in his book describes how the geneticists separated themselves from the 'broad based science' and of course Donald and ABRO drove the new genetic approach which Carter left Australia to get away from.

Richard Carter also confirms after talking to his father's former colleague, that in the latter years when Donald cut off the money to Carter, he worked on his historical research during working hours in his ABRO office in South Oswald Road, as well as in his spare time at home.

Carter at Edinburgh

Leaving Prospect in 1954 and going to Leeds in 1965, Carter must have done eleven years at ABRO, and clearly an early priority was to get some fine-wool Merinos for research.

Dr Angus Russel who worked at ABRO at that time says that Donald and Carter were never great mates, and whatever the reasons, there was bound to be a bit of good healthy trans-Tasman rivalry between them! But then Donald was not great mates with anyone from what most folk can remember.

I was not aware of any detailed wool biology going on at ABRO as I thought all the British work was done at the Wool Industries Research Association (WIRA) in Leeds under AB Wildman.

Sourcing the best Merino genetics

The obvious place for Carter to go for his sheep was the land he had left behind- Australia where nobody would have had a better knowledge of the different Merino strains available. But the export of Merino sheep, and particularly rams, was banned from the main Australian continent as growers didn't want anyone to start up in opposition to them.

But Tasmania was open for business, and they also had the finest woolled strains of Merino. Confirmation of this comes in the introduction of a paper: Slee, J. & Carter, H.B. (1961). J. Agric.Sci. 57, 11. A comparative study of fleece growth in Tasmanian Fine Merino and Wiltshire Horn ewes.

'On a proposal made by one of us (H.B.C.), the Agricultural Research Council acquired a small breeding flock (three rams and twelve ewes) of Tasmanian Fine Merinos strictly for research purposes under agreement and through the courtesy of the Commonwealth Government of Australia. These animals left Tasmania on 29 March and reached England on 12 May 1955. This made possible, probably for the first time, the study of these two breeds under similar conditions and this has been done up to the present at the Dryden Field Station of the A.R.C. Animal Breeding Research Organisation, near Edinburgh.'

Then the source is confirmed by a paper in Nature: H.B. Carter & J. Slee. Nature, Vol. 194, 4824, pp. 215-216. April 14, 1962. An Unusual Bi-paternal litter in sheep from a natural double mating. It states that - 'a single Merino (imported May 1955) from the Valleyfield stud in Tasmania.'

It would be interesting to find out what kind of a challenge Carter had to get his sheep into UK. It could have been much easier than taking sheep the other way, because of Scrapie and Foot and Mouth disease from which Australia is free.

It would be tempting to suggest that a fair bit of diplomatic arm twisting must have gone on but although Carter was a determined researcher, his obsession with attention to detail would have made sure all things were done correctly, as he had a lot at stake in his research plans for ABRO.

Angus Russel is certain that the Merinos came into UK legitimately, but on the strict understanding that they would only be used for research purposes, and that none would be sold for breeding.

Then a real pearl for me appears in Carter's thanks (in the Author's Notes of his book - see later) to 'The Agricultural Research Council, in assisting my own smugglingoperations'. I wonder if this was a bit of 'tongue in cheek' referring to the earlier antics of King George?

Where did the Merino genes end up?

Boaz's book confirms that at Leeds they were slaughtered because of Johne's disease, other than the ones that had been distributed for outside trials.

Whether the ARC was still responsible 'on paper' for the sheep and their eventual disposal after they left their approved Edinburgh base, (or even if they knew or cared) would be interesting to know. As far as ABRO was concerned - you could imagine it being a case of 'out of sight- out of mind'and hoping that ARC would either never find out or have lost interest.

While at Edinburgh, about 6-8 sheep were 'borrowed' by a scientist for some reproductive physiology research, and were not returned or slaughtered (as was supposed to happen). These sheep ended up on a local farm owned by a 'canny Scot' (Willie Crawford) where they increased to a flock of hundreds. About 60 wethers were kept indoors by Willie to produce very fine wool which was sent to Italy for spinning and then woven into fine suiting by Reed & Taylor of Langholm. This was sold locally for one thousand pounds sterling a suit length.

Carter clearly acknowledges 'the support of the Agricultural Research Council' in getting his sheep from Australia. This must have taken a fair bit of time sourcing them, dealing with all the import regulations, transport, quarantine, etc.

It would be interesting to know if Carter applied for the money either before he left Australia or as soon as he got to Edinburgh. The ARC was always tight with their cash, so he must have made a good submission which presumably would be about what superfine genes could contribute to British farming - a repeat idea held by a former King! Merinos would be the obvious choice and nobody would be better informed as to where to locate them.

Family Information on H.B. Carter kindly provided by Richard Carter

- Harold Carter married Mary Brando-Jones in 1940. Harold was in his early research years with CSIRO and Mary had newly arrived in Australia as a young medical graduate from University College London.

- Harold was a fourth generation Australian.

- The Carters had three sons born in Australia and they all went to Edinburgh in 1954 to live as tenants in an apartment in Penicuik House.

- After Carter moved to Leeds, Mary had accepted a medical consultancy in Aberdeen and they both commuted to meet at home in Edinburgh each weekend to the family home in Penicuik.

- The family knew that Carter's years at Leeds were not happy although he did a good job of hiding this from them. He was probably suffering from a state of depression and certainly had stomach ulcers while at Leeds. Leaving Prospect, and then things not working out at ABRO, and then ending up in limbo at Leeds must have frustrated his meticulous standards and ambitions.

- After retirement near Bristol, he finally had a series of strokes which left him paralysed, so went into a nursing home from 2002 to his death on 27 February in 2005.

- Carter's historical research was done entirely in the evenings when he returned from work and at weekends. He worked on his book with incredible speed.

- He rented an unoccupied labourer's apartment in Penicuik House which became filled with his typically highly organised files and collected documents.

- This archive is currently stored in 40+ boxes and cabinets awaiting, hopefully, transport to a research museum (The Power House Museum in Sydney).

Carter retired in 1970 with his wife Mary who had taken up a a medical consultancy as Senior Psychiatrist with the Somerset National Health Service, to a house in the village of Congresbury near Bristol in Somerset, until he went into a nursing home in Weston-super-Mare for three years until his death.

For a period in the first decade after retirement he was a consultant to the company of Sir James Hill & Sons. He and his wife became close friends of Francis Rennell (Lord Rennell of Rodd) who was himself very interested in sheep matters.

At the same time, Carter was developing the Sir Joseph Banks Archive in the British Museum - now effectively inherited by Neil Chambers with whom my father worked in his latter years. From this time, effectively from his retirement, he worked intensively and virtually exclusively on the life and work of Joseph Banks, culminating in his second magnum opus, the Bank's biography - 'Sir Joseph Banks' published in 1988.

'My Merino Story' by T.G. Boaz, M.B.E., M.A.

This 38-page booklet is available from Geoff's daughter, Rosemary Boaz at (info@rhyddbarn.co.uk). It's a great record of how Geoff after meeting Carter again (by chance), got his help to select some Merino foundation ewes (15 of four different ages) and two rams to start Geoff's 'Rhydd Green Merinos'.

Geoff's text:

'I learned that he (Carter) had an interest in a flock of Merino type sheep at the Cotswold Farm Park and on the adjoining Bemborough Farm of Mr Joe L. Henson. These sheep had been transferred there after the disposal of a flock established at the Rodd, near Presteigne, Radnorshire by Lord Rennell and Harold Carter in 1965.'

So here's proof of Carter getting involved with Lord Rennell in 1965, the year he and his sheep arrived at Leeds. I wonder if the ARC knew about that - or maybe they didn't care.

Request for money from BWMB

Geoff reports in his book how he made a last attempt (before he retired) to preserve the Leeds flock by applying for money to the British Wool Marketing Board (BWMB). The answer was no! Geoff comments that 'everyone connected with the BWMB was extremely skeptical about the value of Merinos in this country'. These could have been the comment's of King George III or Sir Joseph Banks.

Geoff Boaz with his Merino flock at Rhydd farm

Geoff Boaz with his Merino flock at Rhydd farmIn the latter stages, the Rhydd Green flock introduced Dorset Horn and Ryeland breeds to cross with the Merinos, before the purebreds were sold off.

Dispersal of the Rhydd Green sheep

In the back of the Boaz book, there are detailed records of where all the sheep went to throughout the UK between 1980 and 1991, as well as 2 rams and 3 ewes to the Falkland Islands in 1987.

H.B. CARTER'S BOOK

Remembering back to my days at Leeds 40 years ago and the Carter saga, I thought I should find a copy of Carter's book on His Majesty's Flock. I was surprised that there were no copies in New Zealand, but I managed to get a copy from Australia with the very musty smell of age about it. I was blown away with the amount of work that must have gone into writing it.

I've only blogged the bits I found fascinating, rather than writing a formal review.

What's the book about?

In the 1700s, Britain's wealth was based on growing, processing and exporting wool to most parts of Europe. The Speaker of the House of Commons still sits on the 'woolsack' to remind the nation of our past dependence on the sheep.

To boost the quality of British cloth exports, fine Merino wool was imported to blend with the British sheep. From the King (George III) downward were worried that the supply of wool would be cut off because of politics and war between England, France, Spain, Portugal, Holland and others. It didn't take much to start trouble.

So the King decided to bring some of the golden fibre that grew on the Spanish Merino to Britain - and he asked his loyal servant Joseph Banks to do the job. Sir Joseph delivered, but with quite a few hassles on the way (to say the least!). In the process Australia and New Zealand were stocked with these incredible sheep.

The book's jacket design

The jacket design by E.D. Roberts depicts a ram's head drawn from a Spanish Merino of 1790, the crown on the spine is that of George III and the symbols on the back are the brands of the famous Negretti and Pualar cabanas (flocks). The colours jointly symbolise the Royal House of England and Spain. I note that Mr Roberts from the Institute of Animal Genetics at Edinburgh is also thanked by Carter for help with maps and diagrams.

Carter’s background (from flyleaf of his book) 1964

‘H.B. Carter is a member of an Australian family which was established in Victoria and Queensland in the forties and fifties of last century. Born at Mosman in sight of the waters of Port Jackson he graduated from the University of Sydney in 1933. For a few years he lived mostly as a bushman first on the staff of a large pastoral company and then as a University Research Fellow. Later as one of the first Australian biologists concerned specifically with problems of sheep breeding and wool production he worked for some years with the Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organisation.

Over the period his work was almost equally divided between close laboratory studies and fairly extensive field work over the sheep and cattle country of the Commonwealth.

Living now in Great Britain with his wife who is an English psychiatrist, and their three sons, his scientific interests have become somewhat more international in scope. The present theme however arises rather from the background work pursued to its ultimate origins in Western Europe’.

At CSIRO, a friend when there as a student remembers Carter as a God-like scientist in the wool area who did not converse with students. That was the formal style of things in those days. Scientists wore white overalls when out in the field and the lesser fry wore green ones he said!

Carter’s ‘Author’s note’

This is a good indication of how much work went into the book. Seeing all the folk he got involved in his project is mind boggling, and of course in those days there was no accounting system to allocate costs. Who he paid for their help and who did it for free is not noted.

Carter thanks Miss Frances Redgrave for 'her speed and precision in producing order out of my tangles typescript'. Richard Carter said his father taught himself to type with two fingers, and that he personally transcribed and typed out every single Banks et.al. letter. He typed up the redrafting of the book manuscript and continued this pattern for the next 40 years of his active scholarly work. Richard suggests that he would get the final copy professionally typed that he would certainly have paid for himself. He was that kind of man Richard stressed.

First on Carter’s list of thanks is Her Majesty the Queen for Her ‘gracious permission to use material in the Royal Archive’. Imagine the sweet-talking letter he would have to write to get into that treasure trove? Then there’s mention of librarians, museum directors and staff, keepers of manuscripts from all over the place, the Met office, Geographical Institutes, University of California's photo lab 'for deciphering original documents', and many many more - all to be thanked for their assistance. I wonder how they all viewed his request over which must have been a very long time.

Of special interest to me is his thanks to Prof. C H Waddington, Director of the Institute of Animal Genetics at Edinburgh – ‘owing him much over a long period’. That would certainly be true.

Then he thanks J P Maule, Director of the Commonwealth Bureau of Animal Breeding and Genetics, which was housed in the same building for his help. Maule was a wonderful helpful person who had traveled widely, and the Bureau was the source of all the research on animal breeding and genetics, which it published regularly in ‘Animal Breeding Extracts’. Maule's help would have been massive.

Carter dedicates the book to his wife which would certainly have been justified with the midnight oil he must have burned on it? His historical research was clearly his major hobby taking up every hour of his spare time, according to Richard Carter.

Sir Joseph Banks

What an incredible man Banks must have been. The work he must have done, in they days on no technology is breathtaking.

- Home residence: 32 Soho Square, London.

- 1st Baronet. Knight's Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (G.C.B)

- 1743-1820 (57 years).

- Landowner in Lincolnshire, Derbyshire, Middlesex.

- Botanist, agricultural scientist

- Explorer around the world with Captain James Cook RN.

- Enthusiastic lover of Polynesian maidens

- President of the Royal Society (PRS) 1778-1820.

- President of the Merino Society 1811-1820.

- Chairman of Lincolnshire Wool Commission.

- Lifetime sufferer from gout.

Imagine being in the lab with the preserved carcass of a kangaroo and a platypus on the bench and asking his helpers for some initial suggestions on where these creatures into the overall scheme of things? Who would have dared to open their mouth?

Wool problems

Don't think that wool problems are a modern feature since the days of synthetic fibres. Wool rows were going well in the 17oos, and Carter describes this in great detail.

The situation is not easy to get your head around, as was so much infighting first within England (West of England, West Riding of Yorkshire and East Anglia), and then between countries (England, France, Holland, Spain, Portugal and others).

Yorkshire had inherited the worsted trade from its birthplace in Norfolk. Lancashire was the home of cotton and the West of England was the home of the finer 'broad cloth' woven on wide looms. The imported fine Merino wool was used in this trade. Steam power and mechanisation was coming in to revolutionise the industry.

Sizing up the opposition

Banks being a researcher, analysing the state of play. Carter sums this up well.

Carter Page 42

'Banks tried to find the facts both at home and abroad, in agriculture and in the woollen industries, which might shed light on what he believed, were too many unsupported statements designed to dupe the Legislature and the nation.

They (Lincolnshire Wool Committee) could find no evidence to support the old and stale notion that the French could not make merchantable cloths of their wools without and admixture of what the English manufacturers and growers together were fond of imagining was superior English staple'.

Carter Page 44

'England had for upwards of one hundred and forty years set a legal wall about her sheep and their wool under the illusion that there was no wool like English wool and that, denied the blessing of this magic staple, foreign cloth manufacturer was condemned to permanent inferiority. There was one qualifying thought. The fine staple of Spain in some quarters at least, was reluctantly conceded to be the exception'.

Banks's letter writing

In the light of the many ways we can send messages today, it's amazing to think how 'information transfer' was limited to the letter, written in ink by quill pen and then delivered by messenger or postal service.

Banks must have spent a large part of his life writing letters, and it's wonderful to think that they were still available to Carter who got many of them transcribed in the book. Carter describes how Banks at one stage 'instituted the first stage of what became an extensive foreign correspondence on matters concerning sheep and wool'.

He sent questionnaires to Hamburg, Hanover, Gottingen, Leipzig, Amersterdam and Abbeville where wool was processed into cloth. Apparently he got quick responses, even though there was one of the many wars going on at the time.

Farmer meetings

Other than letters, meeting and talking face to face was the only other way to spread information, and the most famous agricultural meeting was the Woburn Sheep Shearing. Carter has put the famous engraving of the 1804 shearing by George Garrard, A.R.A in the front of the book. It shows Banks and some of his contemporary agriculturalists with specimens of Spanish Merinos which are being shorn to weigh and inspect their fleeces.

First modern scientific breeder

Carter spends may pages reporting what went on in France and the importance of Louis-Jean-Marie Dauberton, FRS, 1716-1800. He is officially described as a 'naturalist' but served in the Chair of Rural Economy at the Royal Vet School at Alfort in France.

In 1776 he was asked by Louis XV's Controller-General of Finance to start research on wool improvement. As Carter says 'an early modern example of the harnessing of science to a problem of agricultural and industrial importance in the national interest'.

Carter reports that 'he established Montbard as the first experimental station in the world and was the first modern scientific breeder of livestock whose work has present-day relevance'.

That sure is some CV!

The arrival of Spanish Merinos on British soil

The bulk of Carter's book provides the incredible detail of this story. The work involved in sorting out this detail must have been mind-blowing.

He describes (from transcripts of letters) how the sheep were sourced in France and Spain between 1788-1791 and often the intrigue involved, their route to England, on what ship and how long it took, where they embarked and how they got from the port to the King's fields at Windsor, Kew and Richmond. The name of the shepherds accompanying them is also known in many cases - especially those who went to England with the Spanish import that were smuggled from Spain into Portugal and left from Lisbon for the Thames.

Carter describes in fascinating detail the role of Pierre-Marie-Auguste Broussonet, FRS, 1761-1807, botanist and zoologist. He has done an apprenticeship under Banks in London on fish and then went back to France from where he kept sending plant specimens back from his travels. Broussonet was the person to send Banks two Spanish fine-wool sheep, a ram and a ewe, each with an iron collar stamped with Banks's address in London. They were consigned from Rouen and arrived at Spring Grove near Houndslow in Middlesex.

These were the first real Spanish fine-wool Merinos to set hoof on English soil. They were a gift from the French Scientists at Alfort to the President of the Royal Society for his own small private experimental flock. Note they were not for the King of England.

First crossing experiments

Banks then had to get some trials organised to see how these Spanish Merinos could improve British breeds. So he gathered a diverse range of sheep at Houndslow Heath to party with the ram. Presumably the Merino ewe was allowed to join the sheep with wool that varied in length and coarseness.

He got a few sheep from Caithness (by sea), Southdowns from Lewes, Herefordshire ewes from Robert Bakewell in Leicestershire, two fat Lincolnshire ewes and two horned Wiltshires from Middlesex. Presumably they either walked to London or got a ride in a cart. The ram was certainly not overtaxed by these number and his first lamb crop was born in 1786.

Carter says 'For nearly ten years the Spring Grove flock of Sir Joseph Banks was the centre of a web whose strands spread to many corners of the kingdom'. It was a smart move as the flock was close by the rides and paths of Royalty from Windsor to St James's Park for the King and his Court not to notice.

But as Carter points out that Banks had other things to concern him at the time - such as the William Herschel's telescope and new things that could be seen in outer space.

Sheep travel maps

I frequently got confused trying to remember the different importations and where they all went. So I was thankful for the maps which showed the sheep tracks from the Continent to Britain, then withing Britain. It's amazing where the sheep all came from and where they ended up.

Merino husbandry - shepherds' bad news

Trying to farm Merinos is a challenge at any time, and it's clear from Carter's book that Banks had real problems with the shepherds and the farm managers who had to look after them. Carter has covered his many letters and their replies, and even correspondence with the King.

In my experience with them, they are a vastly different sheep to any other ovines. They are loners and hate to be hassled by other sheep, especially those of different breeds. They are a dry climate sheep and in wet climates their toes grow long making them prone to footrot, they are prone to internal parasites and fungi stain the wool. Banks seems to have had all these problems, as well as deaths through cold in hard winters.

It seems it took a husbandry disaster and death before anyone realised Merinos were different and their feet and wool had evolved in an arid climate under 'transhumance' - where they walked long distances to change grazings at particular times of the year.

Banks must have learned a lot about managing the sheep from the Portuguese shepherds who cam with a big importation of sheep smuggled across the border from Spain. Carter records how he spent days with them.

Banks invented ear tags

This is a wonderful bit of history, and having done my research before plastic eartags where invented I can see the genius in what he did. As more Merinos came into Britain and were distributed around the country from the King's and Banks's flock, Banks desperately needed a reliable identification system.

Painting numbers on the sheep's flank is alright till shearing then you have to repeat the performance, and painted numbers are not always easy to read. The paint also ruins wool, especially as in the 1700s tar would be used and not scourable raddles approved by wool processors.

Banks had a friend in the Royal Mint so he asked him to make some numbered metal disks with clips on to hang in the ear. Bingo! The ear tag was invented.

The King

George III has always had a bad press. School history told us he was 'Mad King George' and 'Farmer George", neither of which were great accolades to urban kids. The film of his life (featuring his mental illness) would do much to help his image.

I remember that Prince Charles is an admirer and rightly so as the Prince has a great appreciation of farming and its contribution to the nation. Banks eventually gave all his sheep to the King, as he felt he could act better as an independent adviser on breeding and wool matters.

The King has a great place in the heart of all New Zealanders as one of our famous Maori warriors - Hongi Hika (who had learned English) sailed to England to meet him, and came away with enough gifts to be able to afford to cash in for a ship load of muskets and ammunition in Sydney on his way home!

Demand for sheep grows

Carter page 282:

'In spite of the war with France, so recently joined after the brief Peace of Amiens, the summer of 1803 was remarkable in the affairs of His Majesty's Spanish flock for an unprecedented demand for it's surplus sheep'.

The demand was such and the business of supplying request from various breeders clearly got too much for Banks and the King so a public auction was arranged - the first draft of sheep going under the hammer on 17 August 1800. More great maps in the book show where the sheep went throughout the land and to America where the War of Independence had caused a big demand for wool for uniforms. Carter found documentation to show that 26,000 Spanish Merinos were shipped to the United States in the frantic trading rush of 1810-1811.

As a Northumbrian, I was delighted to see that the Duke of Northumberland, Sir Hugh Percy, had his name down for a sheep, and Banks selected Ram No 127 for him on 18 August 1800 - the day after the sale. Maybe it was passed in or Banks bought it for the Duke.

In the reference Carter found, the ram is described as 'a very good three-shear sheep which has served the King's flock in 1799 - and one old ewe whose mouth was still sound'.

Merinos to Australia - MacArthur

This is a fascinating bit of the story. Captain John MacArthur (1798-1834) of the New South Wales Corps of Campden Park NSW, could be described as the pioneer of Merino breeding in Australia. The hilarious part of the tale was that in Australia he got into a duel with a fellow officer so was shipped back to Britain for Court Marshall.

When he got this sorted out, he went back to Australia with a gift of sheep from the King - and that big dry continent became the world's biggest producer of fine wool.

Andrew James Cochrane-Johnstone, (1767- 1834), Honorable, Colonel, M.P.,

What a wonderful rogue this bloke must have been, and Carter provides chapter and verse on endless examples of his 'wheeling and dealing'. He was a master speculator and arranged for sheep to be purchased in Spain and France and shipped to all sorts of places, especially in large numbers to America. He owned sheep himself and shipped sick and dying sheep to anybody he thought could be duped.

Carter: Page 355.

'There was, however, no end to the ingenuity of Andrew James Cochrane-Johnstone in creating embarrassing situations. In this he was ceaselessly active, losing no opportunity for turning almost any predicament in which he found himself to some dubious form of monetary advantage'.

The autumn days of Banks, the King and British Merinos

Throughout the book, there's accounts of Banks's frequent bouts of gout and how on many occasions he missed important meetings with sheep breeders, shepherds and managers and the King who in his letters transcribed by Carter showed enormous sympathy for his 'Scientific shepherd'. Both Banks and the King were suffering together.

Carter: Page 384.

The month of November 1810 was darkened for Sir Joseph Banks by the final madness of his friend the King. This was the onset of the twilight for the Spanish flock beside the Thames and for the Merinos in Britain.

The Merino Society

Carter describes how on 7 February 1811, a circular letter was sent around by Banks to all those who were keen to form a breed society - to do what all such bodies do, to promote the breed and the needs of its breeders. Banks was expected to accept the Chair which he did. The Society took on a lot of the responsibilities Banks had managed on behalf of the King.

Carter: page 287

'The Society had a brief career but a more significant place in the history of its period than its critics would accord. It effectively formed a bridge across the uncertain and criss-crossed years before and after Waterloo from 1810-1820 when the whole of British sheep breeding and the wool trade was reshaping to the new industrial order'.

Deaths close the era

The King died in 1820 and Banks died the same year. Banks tried to decline his Chairmanship of the Royal Society because of illness, but the Carter book shows the correspondence from the Council refusing to accept it after 42 years.

Carter's final comments on Banks

Page 406

I thought this was extremely well expressed.

'Whatever there is to be said - and there is much - there can be little doubt now that it was Sir Joseph Banks who placed the Spanish Merino and the essential knowledge of its breeding, management and productive attributes at the industrial disposal of Great Britain'.

That's some compliment when you think of the national economic impact at the time. And then muse on all the other great contributions Banks made to his country and the world. An amazing man!

My final comments on HB Carter

Harold Burnell Carter (1910-2003) was an amazing man too, and needs to be acknowledged for his contribution to the Sheep. I regret now not having more contact with him at Leeds.

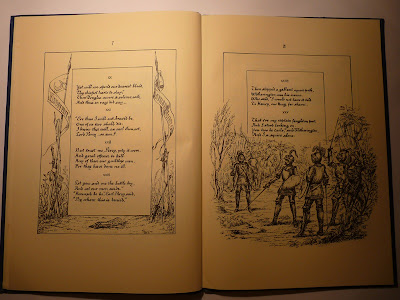

HB Carter the artist

Richard Carter, in fossicking through his father's papers came across these pen and ink drawings, traced from black and white photos - done between 1962-64. Richard says it was around this time that his father was trying to find records of the physical morphology of Merinos from the present through the 18th and 19th Century and the early 20th century studs, all the way back to the 'Golden Fleece'.

Carter's father was a portrait painter so his son Harold had certainly inherited some of his genes.